A new study by the Regional Transportation District reaffirmed that even a bare-bones version of its long-delayed passenger rail line between Denver, Boulder and Longmont would be expensive to build, would carry relatively few passengers, and likely wouldn’t open until the 2040s.

But, the study concludes, the $650 million estimated cost could be lowered and timelines could be accelerated through its partnership with the state and the fledgling Front Range Passenger Rail District, which are trying to plan and build a rail line between Pueblo and Fort Collins.

The two lines could share track and infrastructure between Denver and Longmont, lowering costs, and increasing opportunities for more federal funding for both projects.

RTD declined to make its Northwest Rail project leaders available for an interview, citing its board’s planned discussion of the matter Wednesday night. But the new study and a coming plan for Front Range Passenger Rail service will “form the foundation for a potential joint path forward,” the study’s authors wrote.

RTD and Front Range rail officials have been working together for years. Front Range Passenger Rail District spokesperson Nancy Burke said that would continue, as the state legislature recently required in a bill that also compels RTD to prioritize the unfinished Boulder train.

“Working together provides opportunities for connecting Coloradans along this corridor and it is a big step forward toward the realization of passenger rail service along Highway 36 and beyond,” she wrote in an email.

A spokesperson for Gov. Jared Polis, who lives in Boulder and has been a vocal advocate for the line, said the governor is committed to delivering the “transit and rail opportunities that Coloradans deserve, we’re promised, and that our forward-looking, modern state expects.”

“That starts by finishing the long unfulfilled promise of Northwest Rail,” spokesperson Shelby Wieman wrote in an email.

But RTD is juggling many other challenges and priorities, including the looming threat of Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights restrictions that could lead to budget cuts and an ongoing worker shortage that has limited bus and train service on existing lines.

A cut-rate Boulder train is still expensive, the study found.

RTD originally told voters, as part of its 2004 FasTracks plan, that it would build both a rapid bus line and commuter rail between Denver and Boulder for about $800 million. Trains would extend to Longmont and roll every 15 minutes during busy times, carrying up to 10,100 people a day. Buses would run even more frequently and carry another 16,900 passengers daily.

The agency delivered the rapid bus line in 2016 but costs for the rail line exploded and delayed most of it until the 2040s. In 2021, RTD’s then-new CEO and general manager questioned whether it was worth pursuing, angering taxpayers and political leaders like Polis.

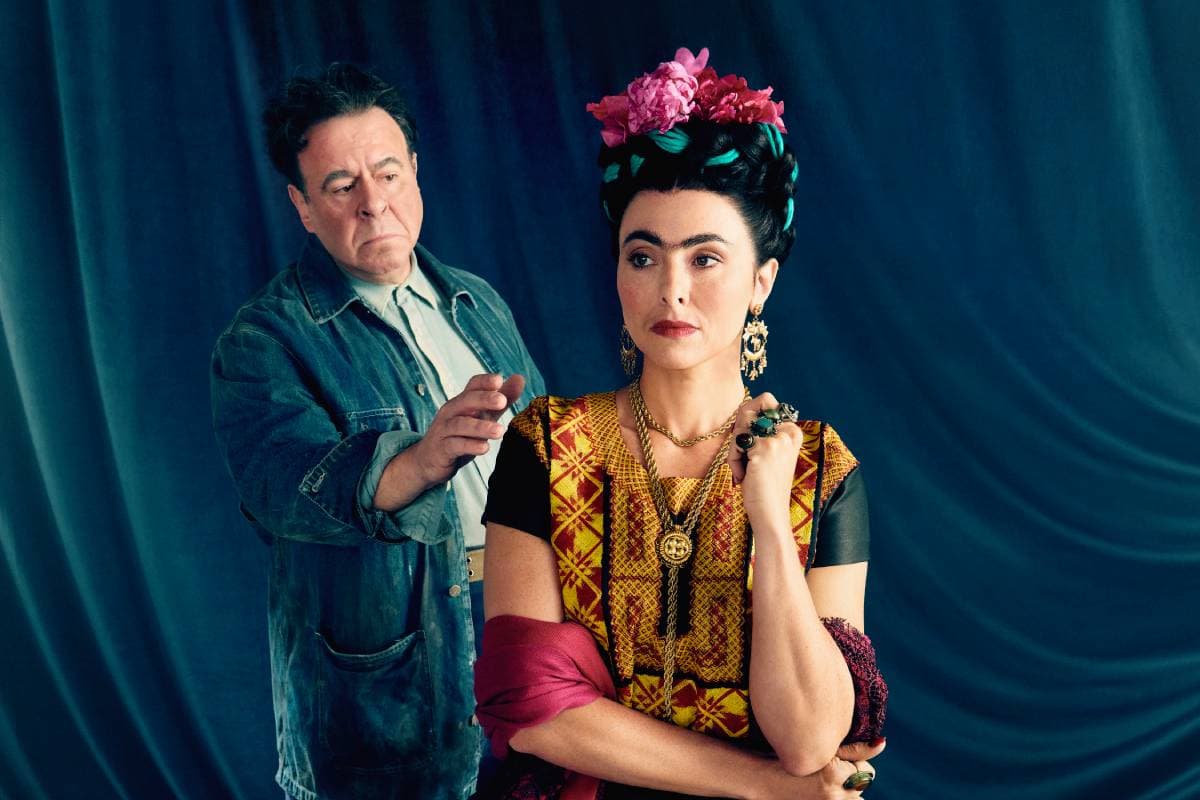

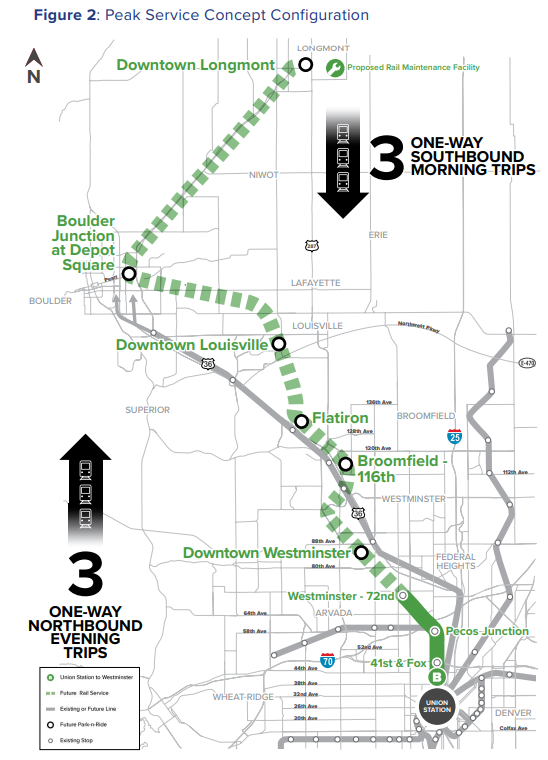

So the RTD board approved an $8 million study of a slimmed-down version of the rail line — just three southbound trains from Longmont to Denver in the morning, and three returning northbound in the afternoon.

The bare-bones line would indeed be cheaper to build — $650 million, compared to the most recent estimate of $1.5 billion for the full buildout. But it would offer relatively little utility for the reduced price, carrying only an estimated 1,100 passengers a day by 2030.

The project’s high costs and low ridership figures have long made it a poor competitor for large federal grants. That continues to be true, the study reported. RTD only included both the rapid bus and rail projects to Boulder in its 2004 FasTracks plan after being pressured to by local leaders, a former executive told CPR News.

The line would also be extremely expensive to operate given the number of riders it’s projected to serve. Annual operating costs are estimated to be between $12 million and $16 million, or up to $57 per rider.

In comparison, RTD says it cost about $8 per passenger to operate its light rail and commuter rail lines in 2023. Its most popular local bus lines cost less than $3 per passenger to run in 2018 according to a once-annual line-by-line subsidy report that RTD no longer publishes.

RTD does not “currently have sufficient funding” to build the rush hour-only commuter rail line on its own, the study said. The agency has about $190 million saved for rail projects and said in a presentation to be made to its board Wednesday that it would have to issue new debt to cover construction costs. That could lower its credit rating and cost about $40 million yearly to pay down.

Operation costs would have to be “offset with reductions elsewhere absent additional funding,” the presentation said.

One key variable is still unknown, too: the cost to use the freight line between Denver, Boulder and Longmont.

The agency has always intended to use BNSF Railway’s freight track to the northwest, but badly underestimated what that would cost to lease. BNSF shocked RTD officials with a quote of $535 million more than a decade ago, a key reason behind the project’s delay.

“They wanted an awful lot of service, which meant an awful lot of capacity had to be built, and that was expensive,” a former BNSF official told CPR News in 2022.

RTD hopes that rush-hour only service could reduce those costs. They still need to be negotiated with BNSF so RTD instead estimated them, drawing on an agreement BNSF made for commuter rail service in Minnesota.

The new study puts just the right-of-way and access easement at $82 million, plus more than $200 million more for infrastructure upgrades like new side tracks, signals and stations along the line.

The Boulder line would also require costly new locomotives and train cars. RTD’s existing commuter-rail trains, which are powered by overhead wires, won’t fit under existing structures on BNSF’s track, the study said. It instead recommended that RTD spend $140 million on five new train sets, likely cars pulled by a diesel locomotive. Those would also require a new $90 million maintenance facility.

Three train sets would sit idle outside of the morning and evening operating windows. The other two would be set aside — one ready to be deployed in case of emergency, and the other in the shop for required maintenance.

That plan is not an efficient use of resources, argued Jack Wheeler, president of the Colorado Rail Passenger Association.

“Simply put, I believe more can be done with the trains and investments made in this study,” which, Wheeler said, lacked vision and innovation. “Weekend service and at least a morning departure from Denver with a midday return would be possible.”

RTD’s study did examine how to expand service, and concluded it was possible — but would cost more money.

The new study sought to establish a “common set of facts” on what is necessary to launch the slimmed-down line, RTD executives have said for the last few years. Whether the line is still feasible now is a decision for the board to make, the study’s authors conclude.