Peak Curiosity is a community-driven reporting series from 91.5 KRCC. We ask listeners to submit their questions about the Pikes Peak region and Southern Colorado, and then we answer them.

When homesteaders and settlers arrived in Colorado, they were eager to name the natural features they found here. While the names they chose are familiar to us now, the stories behind those names are less so. For our latest installment of Peak Curiosity, listener Kathy Pranchack asked about one of those stories.

“I regularly hike this mountain called Mt. Esther, and I’ve always wondered how it got its name. Who was Esther? Why was the mountain named after her?”

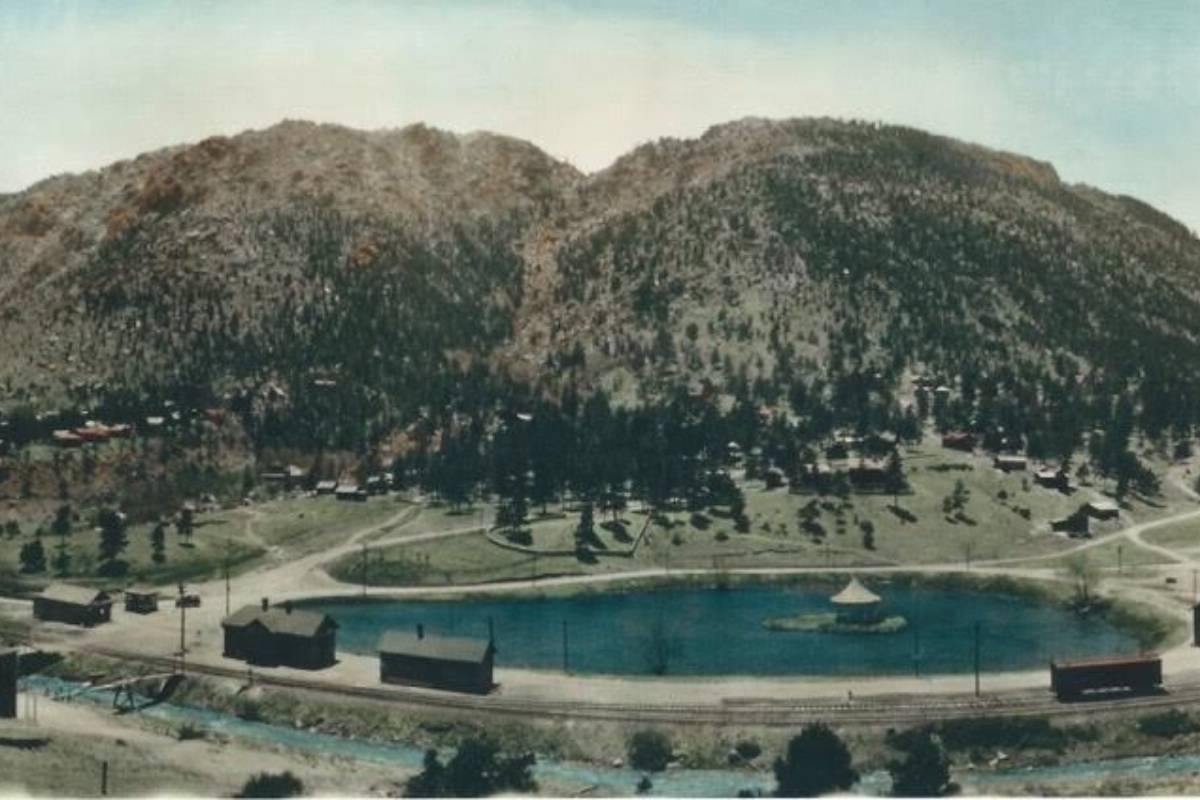

Mt. Esther is a small peak near Green Mountain Falls, a lush mountain town filled with log cabins, 15 miles west of Colorado Springs up Highway 24. As you look southwest from the lake in the center of town, Mt. Esther blocks your view of Pikes Peak.

“The one straight ahead is called Mt. Rebecca, and then stream comes through the notch, and that’s where it changes to Mt. Esther on your left. Those were both named for homesteaders, who were actually up over the ridge in the Crystola Valley,” explains Claudia Eley, a longtime resident of Green Mountain Falls. She’s also the author of a several volume series about the history of Ute Pass.

“As a child I always came every summer. My family bought a cabin up here in 1910,” Eley says. Their family still has cabins in the area that they rent to tourists.

Homesteaders settled the area in the mid 1800s. They quickly set about giving names to the nearby mountains. In the case of Mt. Esther, Eely says the peak was named after the daughter of a prominent early settler.

“George William Sharrock was her father and he came to Ute Pass in 1872 and had a ranch up there,” she explains. “His home later became called the Junction House, which meant the train stopped there of course and it was the post office and everything else -- there wasn’t much there.”

Crystola Roadhouse, a bar and grill, now sits on the site of the old Junction House.

Kathy Pranchack, our questioner, did some digging herself, and discovered a disturbing story about Esther Sharrock. Esther worked at the Junction House, where she often served Ute Indians who came in looking for food. Apparently, she didn’t like them.

Kathy recalls her research: “One day Esther decided she’d had it, and decided to put soap in her food -- I think it was biscuits or beans or something -- to ward off the Indians. She had just had it in terms of them coming by her place.”

Claudia Eely confirmed this anecdote. To hear Eely tell it, It was a pretty ruthless time. There was also a feud between the Sharrock family and another homesteader -- last name, Benedict. Eely says Benedict burned down several homes owned by Esther’s family.

“We don’t know much about the story, but we know he was not kind to them,” she says.

Louis Yost, Executive Secretary of the US Board of Geographic Names, says his organization doesn't have a record of Mt. Esther on any official maps or in their database.

Unlike nearby Pikes Peak or Cheyenne Mountain, Mt. Esther is not a very well known peak. Eric Swab is a local historian who has collected stories of mountain names. He says he doesn't know much about the mountain. One thing Swab could tell us was about a hydroelectric power station that was on the creek that flowed between Mt. Esther and Mt. Rebecca. It ran from six o’clock until midnight and was supposed to power lighting in the area.

“But when women found out they had electricity they started ironing, which brought the hydroelectric plant to its knees and shut it down, because it wasn’t intended to provide that much current,” Swab says.

Swab collects local stories about how regional peaks were named, but to understand the formal process, we had to go elsewhere. Louis Yost is executive secretary of the United States Board on Geographic Names, which keeps a map of formal names. He says, in the old days, the officials would consult the locals.

“When the USGS went out to map the country, the field workmen would ask questions and ask people the names of the features and go to county offices and look at their records there,” says Yost.

Yost says his organization doesn’t have a record of Mt. Esther on any official maps or in their database. He doesn’t know whether that’s its official name, or just a local one.

Kathy Pranchack thinks it might be a good thing if Mt. Esther is not the official name, given the story about the soap and the beans.

“That's really interesting. In fact, if they want to rename that mountain, I think they should!” says Pranchack.

If you want to see where Esther once stood, you can stop by The Crystola Roadhouse, where the Sharrock’s Junction House used to stand.

If you've got a question about Colorado Springs or Southern Colorado that you'd like us to investigate, submit it below!

_